Netflix recently released their four-part miniseries adapted from Anthony Doerr’s novel, All The Light We Cannot See. No one in my literary circle is talking about this which blows my mind, because one: it couldn’t be more relevant today and two: it’s a gorgeous show, capturing the detailed imagery from Doerr’s descriptions, and powerful acting by perfectly cast actors.

This is one of the few novels that changed me as a writer with Doerr’s poetic language and unusual chronological structure. It made me think differently about how some stories should be told and how to conjure empathy for unexpected characters by creating impossible moral dilemmas.

This miniseries indexes on the last years of WW2 from the fall of Paris and German invasion until the Americans landed on the beaches of Normandy in northern France in 1944. This is not a Holocaust story, rather a committed WW2 story. Instead of focusing on the pain and suffering of Jews, this show materializes the incredible terror of an authoritarian dictatorship, a threat lurking for all of democracy today. Both the book and novel teach us lessons about how to treat others, including enemies, and the real human cost of radicalism.

Synopsis of All The Light We Cannot See

Both the novel and the show are crafted with a braided narrative that follows our two young heroes, Marie-Laure, who is blind and Werner, an orphan and student at a Nazi boarding school. Just as the Germans begin invading Paris, Marie-Laure and her father, Daniel, flee to the home of an uncle, Etienne, and his loyal maid, Madame Manec in Saint-Malo, a small seaside hamlet in northern France. Soon, Marie-Laure is stranded after her father—and constant companion—is arrested by the Nazis.

When Marie-Laure is a child, her father painstakingly creates a miniature model of Paris. She memorizes the streets and buildings to navigate the city alone. Daniel makes another one when they move to Saint-Malo. There is a radio at her uncle Etienne’s, which she learns how to operate. Every night she broadcasts on radio channel 1310, a risk and Daniel know she is safe and waiting for him.

Marie-Laure, now 18, reads Braille navigates without vision, without light, two skills that prove invaluable as the Germans hunt for her, the mysterious girl on the radio.

When we first meet Werner, he is a boy in a German coal mining town, living with his sister, Jutta, at an orphanage run by a benevolent French woman, Frau Elena. As a teenager, Werner gains a reputation as a genius radio repairman around town. After fixing the seemingly unfixable radio of a German officer, Werner is recruited to the National Political Institute of Education at Schulpforta, a Nazi military boarding school.

At first, he is excited to be accepted to an elite school. He looks forward to a future with security so he can take care of Jutta and the orphans at Frau Elena’s. He soon realizes that the Nazi culture he has folded into contradicts his compassionate nature. Unfortunately, he lacks the confidence to resist inhumane commands, to confront the violent bullying of his best friend, Fredde, or his fantasy of running away. Yet, we know he is good as he we watch him gradually fall in love with Marie over the radio.

As the story progresses, Etienne and Maurie-Laure take on a daunting responsibility. After all the radios in France had been confiscated by the Germans, Etienne saved one in the attic of his six-story Chateaux, which he later used to transmit secret, illegal messages across Europe. Since Etienne is crippled by debilitating agoraphobia, the two devise a plan where Maurie-Laure walks her memorized path to the bakery and asks for an “ordinary loaf,” in which a tiny scroll of paper with a message is baked.

Most of the messages contain series of coded numbers that Etienne transmits in the evening, followed by a few minutes of classical music for levity. One day, they received an ironically confusing message that read: “’Monsieur Droguet wants his daughter in Saint-Coulomb to know that he is recovering well.’… ‘What does it mean?’ Marie-Laure removes her knapsack and reaches inside and tears off a hunk of bread. She says, ‘I think it means that Monsieur Droguet wants his daughter to know that he is all right’” (346).

Eventually, Etienne, too, is imprisoned by the Germans and Marie-Laure is left alone. When she can no longer retrieve and transmit messages from the bakery, she begins reading Twenty Thousand Leagues Under The Sea each evening from a book written in Braille over the radio. Werner, who secretly tuned into her evening readings was tasked with locating the rogue transmitter and killing the girl. He pretended not to locate it, and it was this connection that saved her life upon their chance meeting for just a single day.

There are some major changes to the miniseries from the novel, but I found them immaterial as the show maintains the same narrative arc overall, and conveys the book’s intent.

Just like the novel, the show is beautiful. Mark Ruffalo plays Daniel, a devoted and sweet father who enables a world that his daughter can easily maneuver. Hugh Laurie, aka House, plays Etienne, a serious, and mysterious man who has a remarkable character arc. And finally, the part of Marie-Laure is played by Aria Mia Loberti, a debut actor who is blind, herself. The film industry is gradually casting disabled characters with similarly disabled actors, which opens opportunities to those in our society who have been callously forsaken, particularly in the arts.

Enjoying All The Light We Cannot See

There are so many reasons one could point out that make this a “great book,” but I argue that there are three specific variables that differentiate it from one of the many historical novels about WW2.

First, the story alternates between these two protagonists one short chapter at a time. In masterful elegance, the author carries the narrative along in a non-linear timeline: past to future, to the past, to the future, until the past—moving forward—and the future—moving backwards—meet somewhere in the third quarter of the book at the present, and Marie-Laure and Werner’s lives intertwine, albeit briefly. Constantly switching back and forth can be a challenge for even the most sophisticated writers, causing unnecessary confusion and distraction for readers. The miniseries also uses the non-linear chronology. Both the author and the director, Shawn Levy, established characters with pasts, present, and futures so concrete, real people with real lives, the jumps in chronology always make sense. In fact, there’s no better way to arrange this story.

Second, is simply the writing. Doerr’s prose is beautifully lyrical and poetic. In a particularly omniscient passage, Doerr writes:

“We all come into existence as a single cell, smaller than a speck of dust. Much smaller. Divide. Multiply. Add and subtract. Matter changes hands, atoms flow in and out, molecules pivot, proteins stitch together, mitochondria send out their oxidative dictates; we begin as a microscopic electrical swarm. The lungs the brain the heart. Forty weeks later, six trillion cells get crushed in the vise of our mother’s birth canal and we howl. Then the world starts in on us” (468).

In this quote, Doerr describes a biological event, using scientific language in a way that reads like poetry; not a science textbook. It is relevant to note that both Marie-Laure, who is fascinated by sea-life, later becomes a well-known scientist working at the museum where her father had been a custodian before fleeing Paris. Werner, himself, is a highly regarded engineer, who is later placed in the Wehrmacht, tracking enemy signals. This lyrical description of conception is the perfect complement to the characters’ interests in science.

Third, of many possible reasons to love All The Light We Cannot See is the unbiased reference to Nazi propaganda from a first hand source. When we read contemporary novels about WW2, they posit Nazis as a single entity, “The Nazis.” In ATLWCS, the Nazi “marketing strategy” is told from a perspective of fear and contrarianism in literature. It’s not often that we read about a sensitive protagonist, like Werner, who was coerced into being a Nazi. It reminds readers that the Nazis were comprised of people, some downright sadistic whose only goal in life was to destroy the lives of innocent civilians; and then Werner, a quiet boy with great talent, fearful of authority, a hero, but still—a Nazi.

Doerr describes Werner in class with the following dialogue:

“In technical sciences, Dr. Hauptmann introduces the laws of thermodynamics. ‘Entropy, who can say what that is?’

The boys hunch over their desks. No one raises a hand. Hauptmann stalks the rows. Werner tries not to twitch a single muscle.

‘Pfennig.’ [Werner]

‘Entropy is the degree of randomness or disorder in a system, Doctor.’

His eyes fix on Werner’s for a heartbeat, a glance both warm and chilling. ‘Disorder. You hear the commandant say it. You hear your bunk masters say it. There must be order. Life is chaos, gentlemen. And what we represent is an ordering to that chaos. Even down to the genes. We are ordering the evolution of the species. Winnowing out the inferior, the unruly, the chaff. This is the great project of the Reich, the greatest project human beings have ever embarked upon’” (240).

Empathy For Unexpected Characters

This simple interchange, which clearly emphasizes the Nazi obsession with genocide in unrelated context, creates a counter-narrative to Marie-Laure. It also creates unexpected sympathy for Werner by showing the complexity of a disadvantaged boy who didn’t agree with the Nazis’ cruelty, but was also—for a time—freed by his Nazi “adoption.” By exposing the reader to Werner’s environment, we can empathize with him. He was manipulated to be a Nazi and we feel sorry for him. Then he follows Nazi commands that go against most readers’ worldview and we hate him for it. Then he saves our brave, committed, and blind heroine. She, too, saves him, and he is able to face his future.

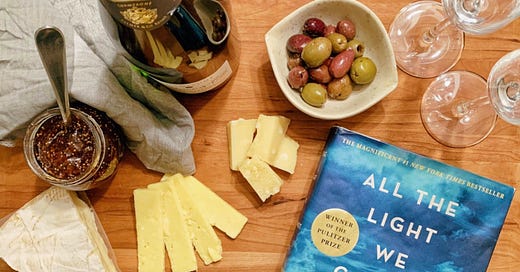

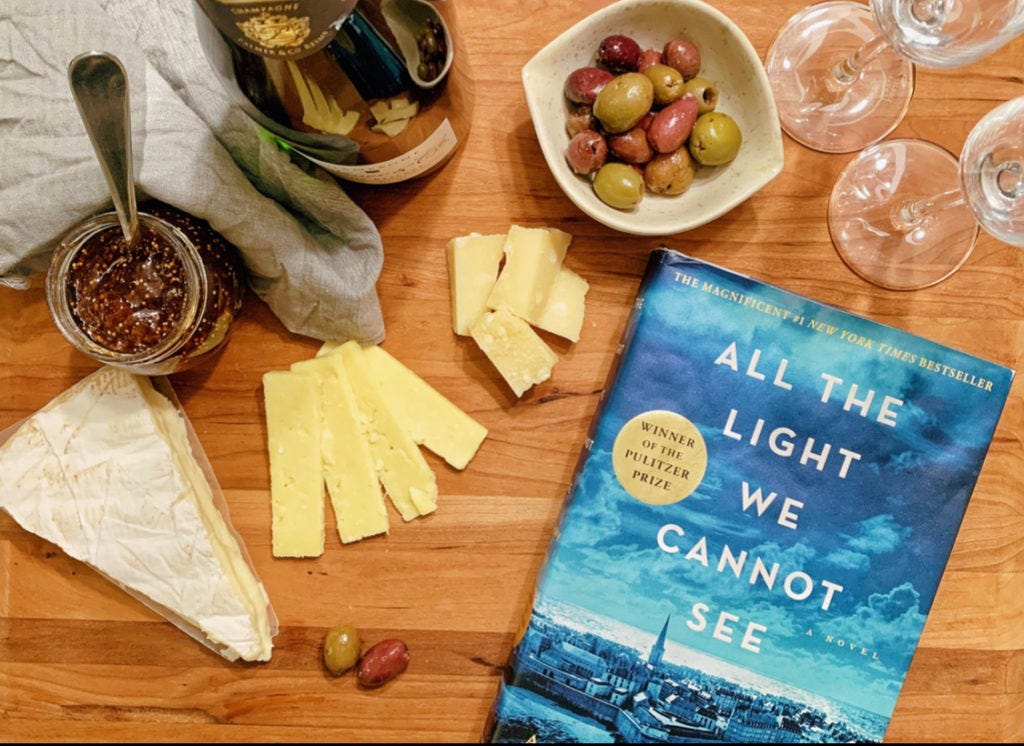

If you are looking for a great show to binge this holiday week—or book to get immersed in—look no further than Netflix or the original novel. Get yourself a snack, some tea, or a glass of bubbly and settle in.

Have you read or watched All The Light We Cannot See? Leave a comment and let me know what you think.